Australia’s green iron ambitions rely on hydrogen

Posted: May 05, 2025

In February, the Australian government announced a A$1 billion (US$630 million) green iron fund, with the goal of making Australia "the center of the global green iron market" and creating "a new, multibillion-dollar manufacturing industry."

Australia’s vision for green iron—that is, iron that’s extracted and processed using renewable electricity and green hydrogen—is bold but far from implausible. The country is the world’s largest producer of iron ore (by a huge margin) and has large swathes of land on which to build renewable energy infrastructure.

Yet in spite of these natural advantages, the fate of Australian green iron is far from assured. Iron and steel prices are stubbornly low; green-ish iron production is growing in other regions, notably in the Middle East; and the roll-out of the hydrogen infrastructure required to make truly green iron is facing headwinds.

Our Industrial Life

Get your bi-weekly newsletter sharing fresh perspectives on complicated issues, new technology, and open questions shaping our industrial world.

The technologies behind green iron

Excavation, transportation, crushing and screening, pelletizing—each step in the iron-making process can in theory be powered by electricity, or made green in other ways. For example, Vale has developed an alternative to the coal-hungry pelletizing process that involves using biomass to produce briquettes.

The crux of green iron, however, is “direct reduced iron” (DRI), the feedstock for the electric arc furnaces used to produce green steel.

As opposed to pig iron, which is typically produced in a coal-powered blast furnace by heating iron above its melting point of 1,538°C, DRI is produced by using a gas to remove the oxygen from iron ore without the iron having to reach melting point.

At present, natural gas is used to produce DRI, but hydrogen could also be used. If that hydrogen is produced using renewable energy, DRI could be truly “green.”

Such a DRI plant is planned in Finland, but the current lack of green hydrogen infrastructure in Australia means any DRI facility in the country would initially rely on natural gas.

Viable green iron depends on hydrogen infrastructure

Analysis by Deloitte and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) finds that the energy source used for DRI has a huge impact on the competitiveness of Australian steel. In a market of all-green steel, Australian DRI can be highly competitive; in the conventional steel market, it isn’t.

If hydrogen-powered DRI is the future, how is Australia’s hydrogen infrastructure build-out going?

Last year, iron ore miner Fortescue broke ground on a green hydrogen plant and has ambitious plans to power operations at its Christmas Creek mine with green hydrogen. But the company has also scaled back its broader hydrogen business and is considering delaying some other projects.

And in neighboring South Australia, plans for a A$600 million hydrogen plant, which was intended to power the nearby Whyalla steelworks, have been shelved in favor of bailing out the steelworks itself. "I'm not going to build a hydrogen plant and have no one to sell the hydrogen to," said Peter Malinauskas, the state’s premier.

That said, investment continues to flow into the sector, and the high-profile cancellations of a few planned hydrogen projects should be seen in the context of significant activity across the country.

“Australia already has a globally significant project pipeline of more than 100 projects announced since 2019,” notes the government’s 2024 National Hydrogen Strategy. “This pipeline is larger than for any other single country. It represents approximately half of all export-oriented projects announced globally. The pipeline is growing yearly.”

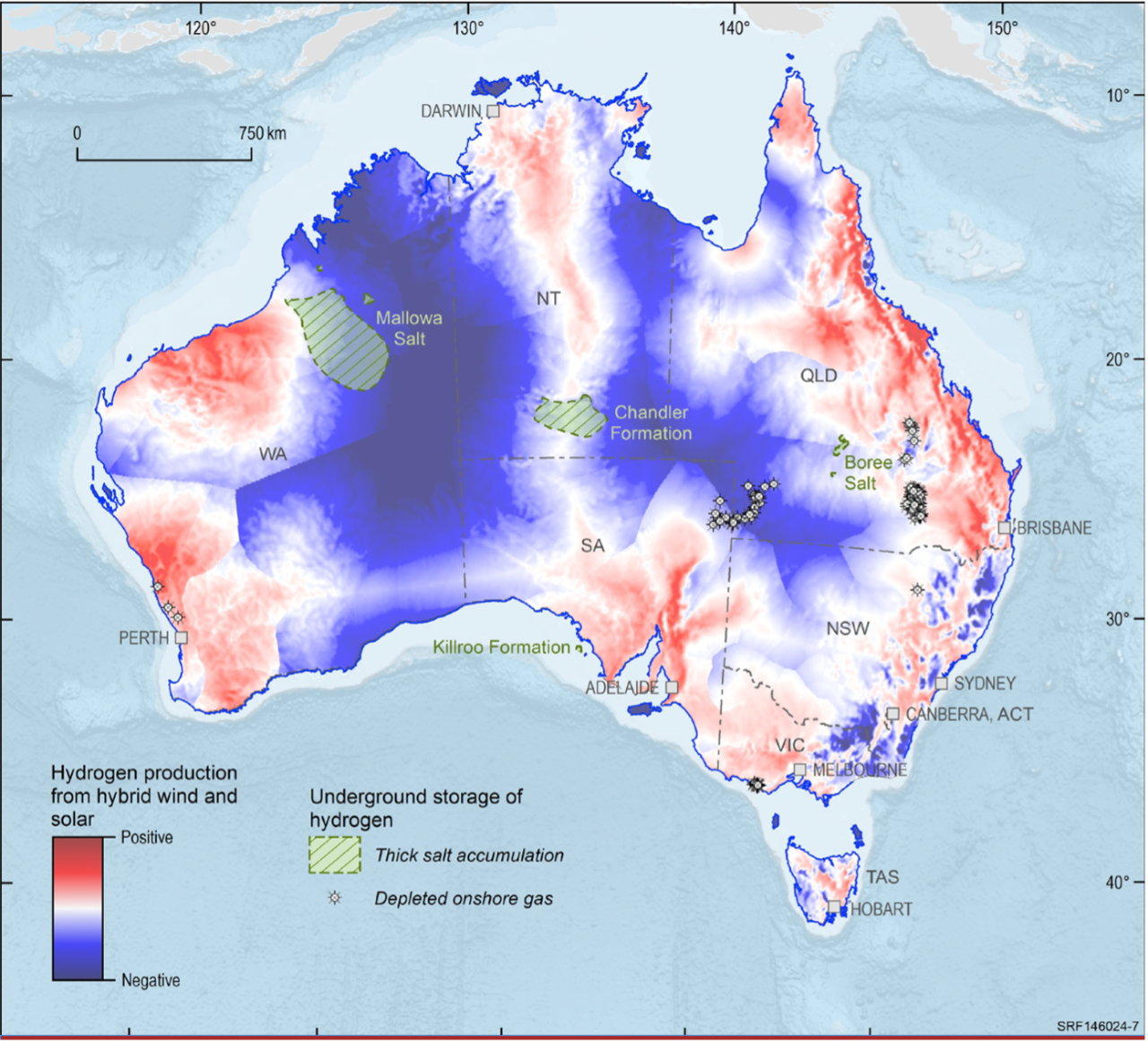

Australia’s hydrogen production potential. Source: Geoscience Australia via National Hydrogen Strategy

Australia’s hydrogen production potential. Source: Geoscience Australia via National Hydrogen Strategy

The government does concede that “most projects remain at the feasibility or engineering stage,” but that is hardly surprising for an industry only just starting to get off the ground.

“As you roll out the solution, the barriers become clearer, but also the ways that you might address those barriers also becomes a little bit clearer,” Climateworks Centre’s Kylie Turner told The Guardian.

Regulation and diplomacy will be key to Australian green iron

Beyond continued investment in hydrogen infrastructure, for the Australian green iron industry to thrive “the adoption of a carbon price mechanism in Asia-Pacific markets is needed,” argues the WWF-Deloitte report.

Environmental regulations, such as carbon taxes, could push up the price of non-green steel while making tax-exempt green steel more attractive.

The WWF-Deloitte report concedes, however, that “it isn’t clear how such a mechanism could be designed and placed into force across the range of high- and middle-income economies across Asia.”

Australia’s green iron ambitions might therefore end up hinging as much on savvy international diplomacy as on the build-out of hydrogen infrastructure.