How London brought its Victorian sewers into the future

Posted: September 22, 2025

London in the 1850s was not an altogether pleasant place.

Its population had recently swelled threefold to more than 3.5 million people, making it the largest city in the world. To its inhabitants, that rapid growth came with painful side effects: the streets were literally running with filth—both human and industrial—as the city’s old open sewers were simply overwhelmed.

Much of that filth eventually ended up in the Thames, and during the summer of 1858, a heatwave made the problem too bad to ignore. A cartoon from July of that year, dubbed ‘The Silent Highwayman,’ shows Death in the form of a cloaked skeleton rowing on the river, dead creatures bobbing belly-up around his boat.

In fact, what became known as the ‘Great Stink’ was killing people, too: waterborne typhoid and cholera had already claimed thousands of lives, even though the Victorians at the time ascribed the deaths to foul ‘miasma’—the smell itself.

The stench rising from the river was so strong it even disrupted parliamentary proceedings. By August, London had had enough and a law was rushed through to create a new unified sewage system.

Our Industrial Life

Get your bi-weekly newsletter sharing fresh perspectives on complicated issues, new technology, and open questions shaping our industrial world.

How the Victorians built London’s first unified sewage system

The task of cleaning up London’s foul streets and waterways fell to Sir Joseph Bazalgette, then the chief engineer of the Metropolitan Board of Works.

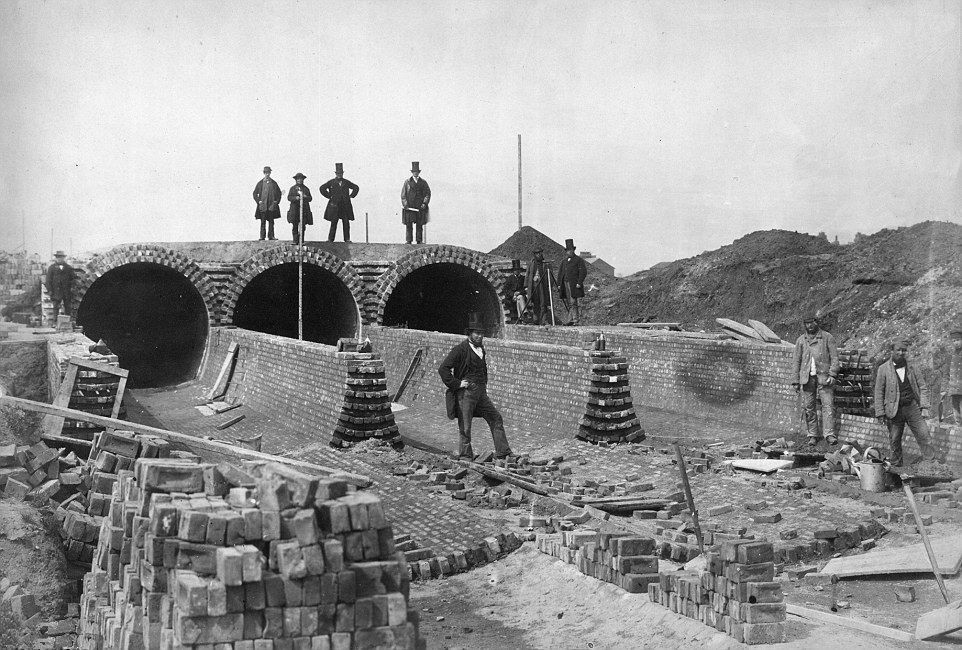

Under his direction, thousands of laborers built more than 1,000 miles of drains, sewers and tunnels beneath the city, plus a network of pumping stations, all using cutting-edge technology for the day.

Mind you, back then, many of the tunnels still had to be dug by hand. To expand the network, workers also reinforced and covered some of London’s natural rivers and streams, many of which now run almost entirely underground. More than 300 million bricks were laid as part of the project, which was so massive that it drove up bricklayers’ wages by 20%.

Building London’s original Victorian sewer system relied mostly on manual laborers.

Building London’s original Victorian sewer system relied mostly on manual laborers.

Previously, waste and rainwater had backed up regularly in the existing channels when the Thames was in high tide, forming cesspools of stagnant sewage. When the river was low, sewage flowed freely, but in turn made up a large share of the water. Under the new system, waste was now more efficiently funneled downstream and dumped far east of London in the Thames’ lower reaches, to be swept out to sea on the ebbing tide.

Bazalgette’s design relied on a set of four large pumping stations to lift sewage from low-lying parts of the city, using the biggest steam engines in the world at the time (some of which, curiously, were named after members of the royal family). Built in ornate Romanesque and Italianate Gothic styles, the stations themselves still look more like colorful cast-iron cathedrals than waste-moving machines.

Bazalgette went much further than just cleaning up the river. He also embanked the Thames while he was at it, reclaiming some 52 acres of riverside land and muddy foreshore, and designed some of London’s most famous bridges. And the system did its job: Once completed in 1875, London’s new sewer virtually eliminated cholera.

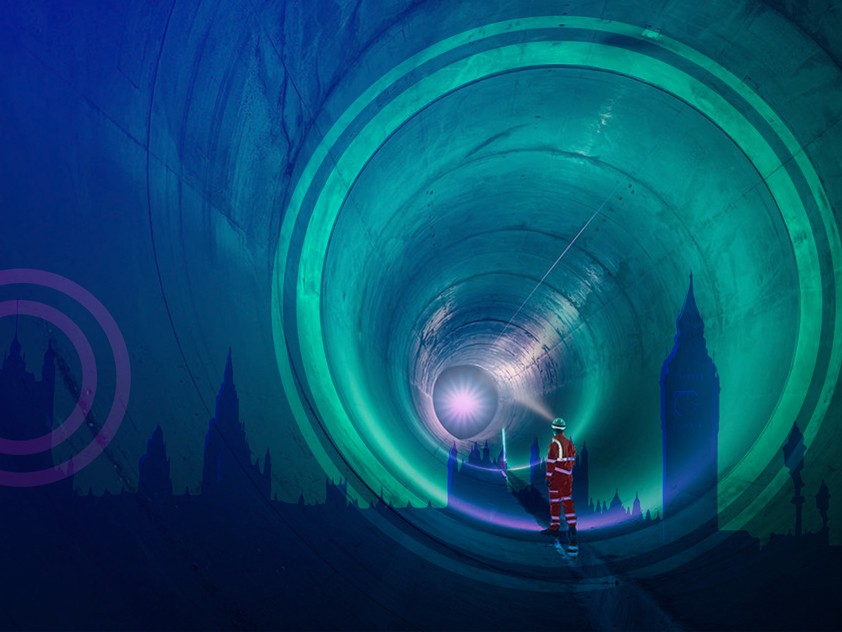

How London’s new super-sewer was built

The Victorian tunnels and pumping stations were so well-conceived that much of Bazalgette’s network has stood the test of time and remains in use today. But after a century and a half of use, the system is beginning to meet its limits. Aside from a much bigger population, now approaching nine million, climate change has started to overwhelm the system, too.

Flash floods caused by heavy rains are now occurring more frequently, forcing the old wastewater network to release raw, untreated sewage into the Thames—as well as many other waterways around the country. Last year, raw sewage spilled into England's rivers and seas for a record 3.6 million hours.

To get a grip on the issue, London started work in 2016 on the biggest update to its sewers since Bazalgette’s Victorian tunnels were built more than 150 years earlier. The plan for the project, officially known as the Thames Tideway Tunnel, involved digging a new 25-km-long super-sewer. It would run alongside a stretch of the river right in the middle of the city in order to intercept dozens of the most polluting overflow tunnels.

The excavation work couldn’t have differed more from the days of Bazalgette, when thousands of manual laborers excavated the tunnels. Instead, six giant tunnelling machines burrowed beneath London to dig out shafts of nearly 24-foot-diameter. Each of the machines was carefully calibrated to cope with the differences in soil composition along the tunnel's route, comprising a changing mix of chalk, clay, sand and gravel.

But even before construction started, engineers faced some daunting challenges. They had to design a tunnel that could not only navigate variable ground conditions and the old sewers, but also find a way through London's underground networks, piers and bridges.

Workers conducted geophysical surveys using ground-penetrating radar and electromagnetic locators to pinpoint utility networks and even World War II bomb shells still lodged in the riverbed. Experts also modeled everything from pneumatics and transients to fluid dynamics and air dispersion.

All that subsurface data was fed into 4D models of the tunnel, which also incorporated schedules for the many different teams working on the project—an innovation Tideway says helped save time and money during construction. The project’s modeling specialists also developed a virtual-reality tool, operated with a simple gaming controller, to identify design or construction issues and train workers in using the tunnel-boring machines. (A free app lets anyone explore an augmented reality model of the boring machines.)

Once the shafts were excavated, remote-controlled machines took over some of the tunnel lining to prepare for pouring concrete, a process traditionally performed manually—marking the first time the technology was trialed in the UK. Tideway is also using autonomous vehicles for regular inspections on the network.

As with the first Victorian network, the impact of the new super-sewer has been instant: Tideway says the tunnel, which was fully connected in February, eliminated all discharges into the Thames during its first four months in operation by diverting some seven million tons of sewage.

Despite the vast gap in time and construction methods, the super-sewer also managed to pay homage to the grandfather of London’s water network. The company overseeing the project was fittingly named Bazalgette Tunnel Limited.