Raising a new Manhattan neighborhood out of thin air

Posted: October 22, 2025

Even more so than in most city neighborhoods, development in Manhattan is dictated by a scarcity of space: The island measures just 23 square miles, which have been densely built up for hundreds of years.

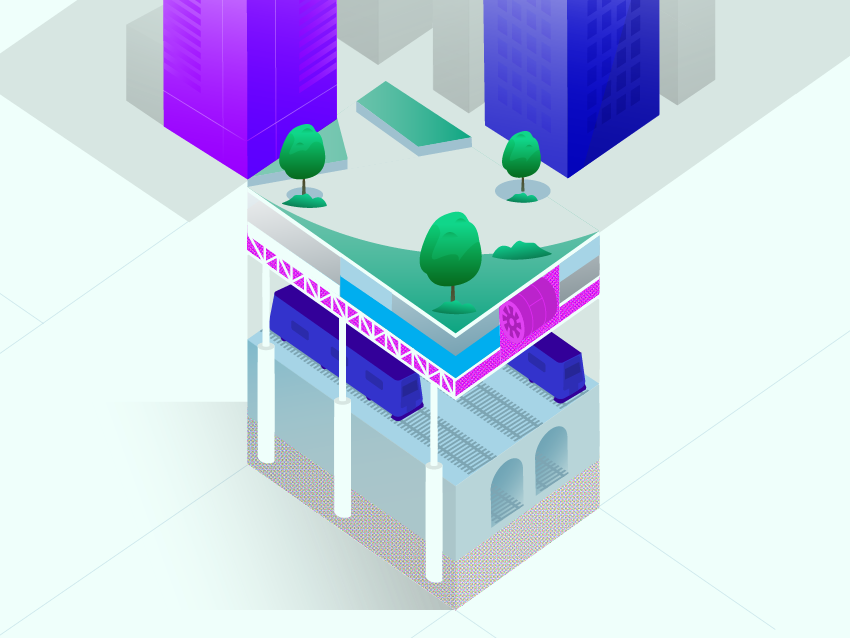

Such paucity made it all the more remarkable when Related Companies and Oxford Properties set out to raise an entirely new neighborhood above a stretch of active train yards on the Hudson River waterfront—by some measure, the largest private real estate project in US history (although the project has also received billions in public subsidies).

The first half of the 28-acre site, called Hudson Yards, has been open since 2019 and comprises six skyscrapers, a shopping complex and a cultural center, all grouped around a central plaza. The developers now hope to add more towers, a school and more public space in a second phase, which has yet to break ground.

Here’s how engineers designed and built an entire district on top of active train yards:

Our Industrial Life

Get your bi-weekly newsletter sharing fresh perspectives on complicated issues, new technology, and open questions shaping our industrial world.

Building atop train tracks

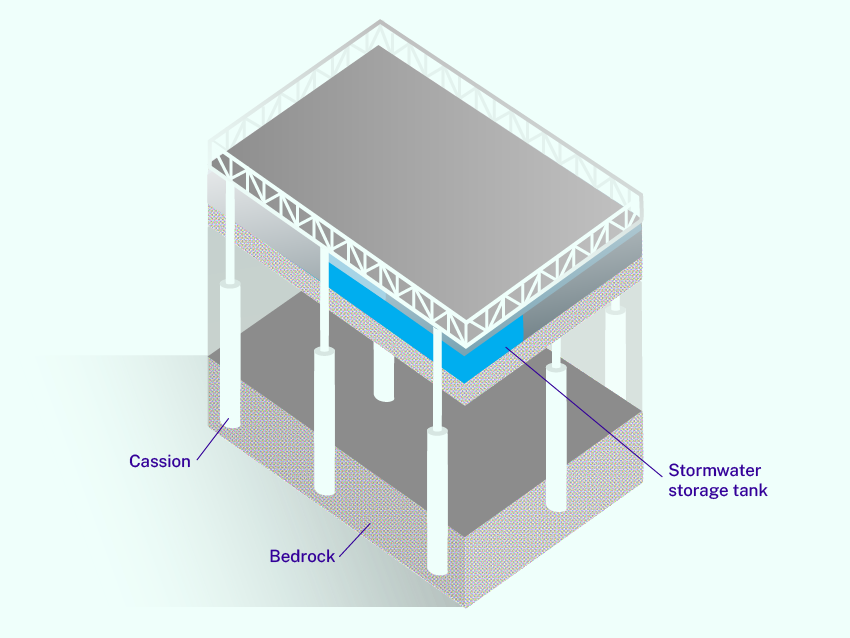

To be able to coexist with the 30 train tracks running underneath, the first section of Hudson Yards had to be raised on a carefully placed platform. It consists of columns and trusses resting on 300 caissons drilled deep into the bedrock below, supporting the new neighborhood and most of its buildings. But, since the caissons had to squeeze in between train tracks, underground tunnels and utilities, only 38% of the site could be directly built on.

“You’re not just designing a building, you’re designing a complete specialty underlying structure to be able to support that. And unless you look out at the western rail yards and see the trains there, you have no idea what’s underneath us,” says Eli Gottlieb, a managing principal at Thornton Tomasetti, the firm that handled the platform’s structural engineering.

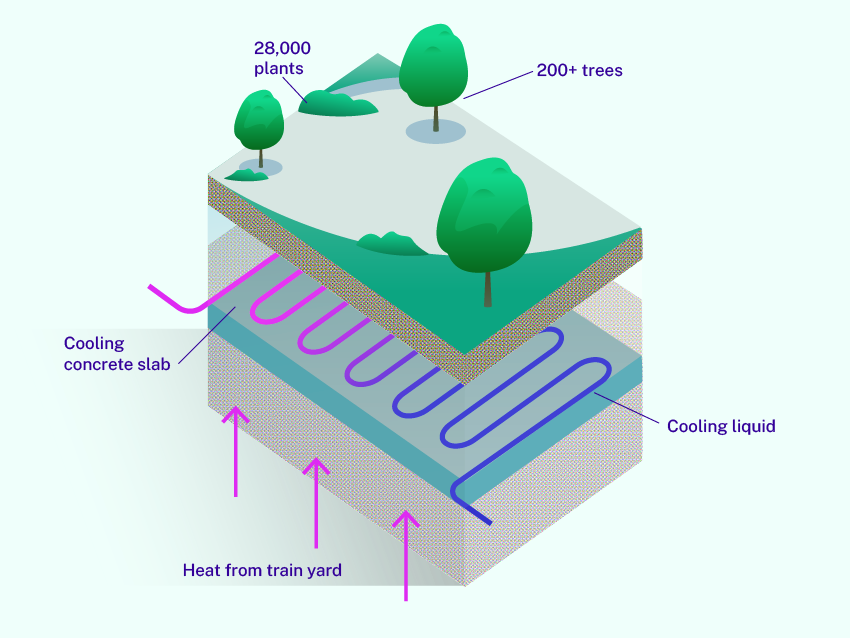

Channeling heat and water

One side effect of enclosing the train yard: a lot of heat. To keep the temperature below Hudson Yards from reaching up to 150 degrees Fahrenheit, engineers sandwiched 15 giant fans—typically found in jet engines—into the thickest part of the platform and connected them to two ventilation shafts. Each one is 40 feet long and 5 feet in diameter; together, they can replace all the air in the train yard in just seven minutes.

On top of the fans, a network of embedded tubes circulates cooling liquids to help keep some 28,000 plants alive across the neighborhood’s parks, including more than 200 mature trees. A 60,000-gallon stormwater tank also collects rain and reuses it for irrigation.

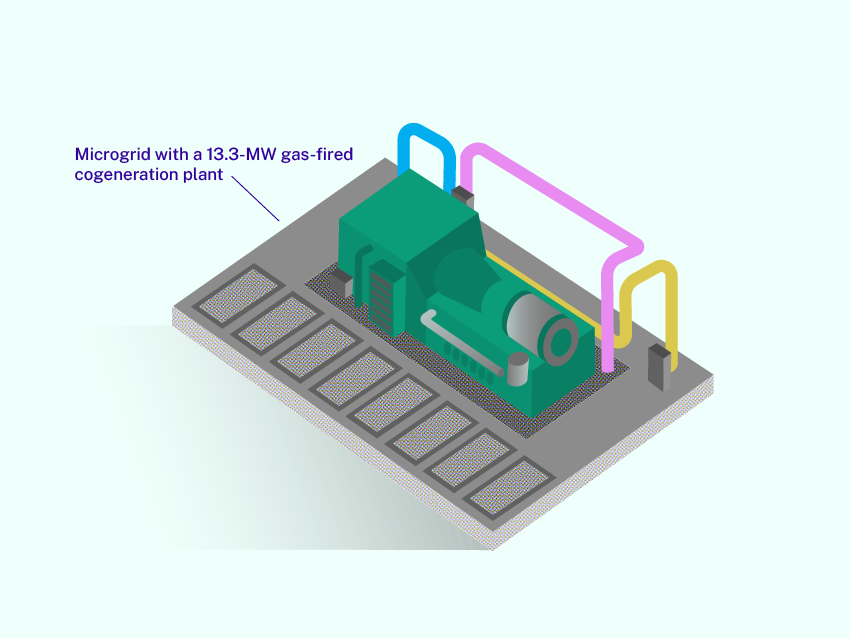

A microgrid for a mini-city

That sustainable approach extends to utilities, too. Hudson Yards has its own microgrid and a 13.3-MW gas-fired cogeneration plant—located on top of its retail complex—to generate electricity. A thermal loop uses excess heat captured from the plant to both heat and cool water for the neighborhood. The on-site generation not only powers Hudson Yards but also protects the neighborhood from outages and blackouts; it feeds power back into Con Edison’s wider Manhattan grid, which is offset from the district’s energy bills, but is isolated by breakers in case of a grid failure.

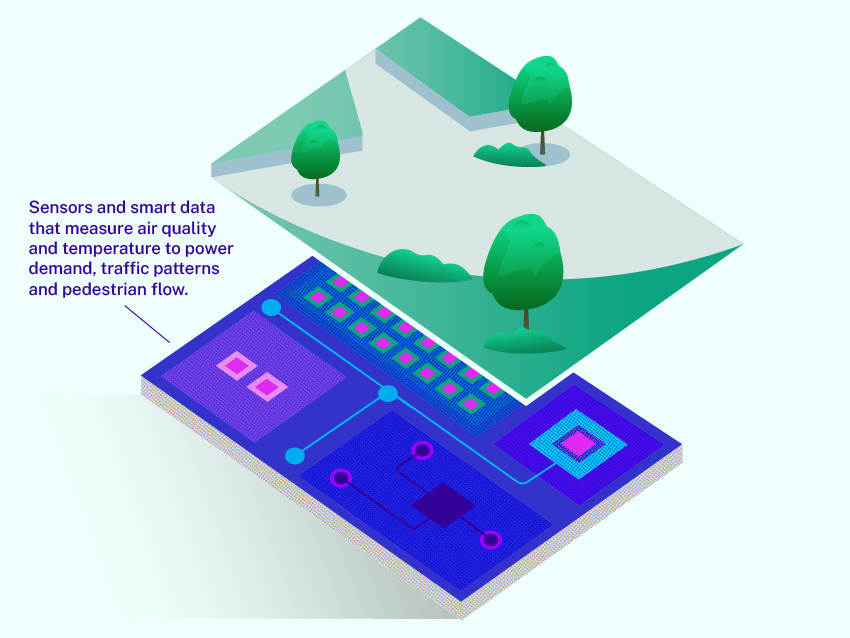

Sensors and smart data

When building the platform and other infrastructure, the developers were keen to integrate data wherever possible, according to Jay Cross, who served as president of Related Hudson Yards during the first phase of the project.

The site’s data infrastructure rests on a fiber loop and includes mobile, cellular and two-way radio communications. In the future, the developers also hope to wire up both sections of the district with an array of sensors to measure and react to changes in everything from air quality and temperature to power demand, traffic patterns and pedestrian flow.

“Converging disparate systems generally requires a spaghetti-work of software and hardware solutions to cohere in just one building,” says Cross. "Because we were creating an entire multi-structure neighborhood from whole cloth, real estate included, we were able to create a cohesive conversation on a single-software platform fed by a unified fiber optic network.”