Drilling for oil and gas offshore: past, present, future

Posted: November 19, 2025

If you were to cruise along California’s famous Pacific Coast Highway, heading west from Santa Barbara towards Los Angeles, you might pass by a small town called Summerland. This unassuming little settlement might not catch the eye for anything except its evocative name—and a rather handsome-looking stretch of beach. But Summerland is, in fact, a major site in the world history of energy production. The Summerland Oil Field, inactive for many decades now, is considered by many to be the first seaside oil drilling enterprise in the world.

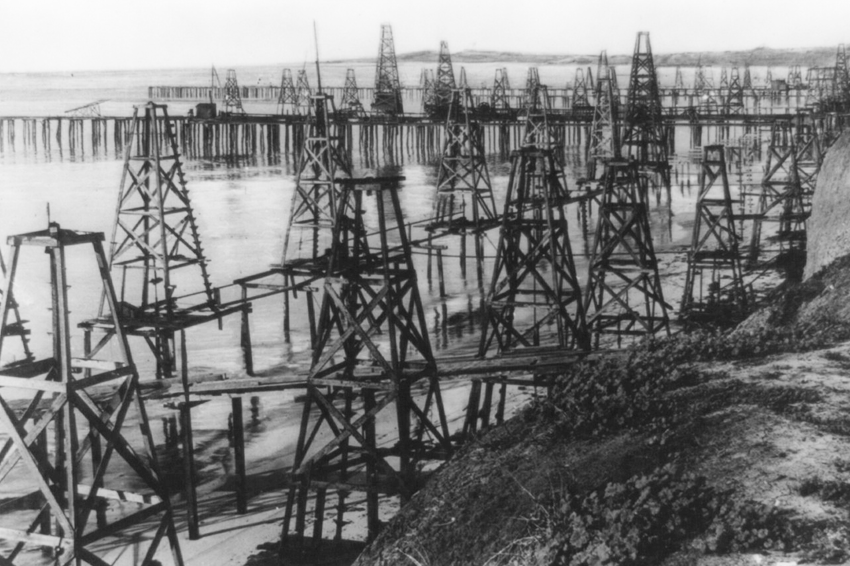

Initially a small religious community, Summerland was transformed by the discovery of natural gas and oil reserves during the 1890s. A wooden pier was built into the Pacific Ocean along with a cable-tool derrick—a hoisting apparatus that supports, raises, and lowers drilling tools to and from the well using a cable—thus inaugurating a brief local oil boom that involved numerous companies constructing 14 further piers and over 400 wells.

Our Industrial Life

Get your bi-weekly newsletter sharing fresh perspectives on complicated issues, new technology, and open questions shaping our industrial world.

Summerland was just one of the early predecessors of offshore oil and gas as we now know it, an industry that accounted for more than a quarter of all combined oil and natural gas produced worldwide in 2022 and has continued growing since: according to Global Energy Monitor, some 85% of last year’s new discoveries by volume occurred offshore. As early as 1891, submerged oil wells had been drilled from derricks built on horizontal wooden structures known as “cribs” in the shallow freshwater of Ohio’s Grand Lake St. Marys. Submerged drilling also took place on the Canadian side of Lake Erie in the 1900s.

Yet it was at Caddo Lake in Louisiana in the 1910s that offshore drilling was first achieved without the use of piers at all. Here, a fleet of tugboats, barges, and floating pile drivers drilled a well that brought in some 450 barrels a day, which Gulf Refining Company accessed using a series of platforms on the lakebed. More platforms and wells were erected then connected to the mainland via pipeline. This pier-less system has been dubbed the first true offshore drilling initiative in America—and probably anywhere.

Barely offshore. Summerland, circa 1920. Wikimedia Commons.

Barely offshore. Summerland, circa 1920. Wikimedia Commons.

The Gulf Coast origins of modern offshore drilling

Offshore oil and gas drilling continued to accelerate through the early and mid-20th century, thanks in part to technological advances like the adoption of steel over wood for drilling structures as well as the introduction of complex rotary rigs—which apply rotational force in a clockwise direction—in place of linear pile drivers.

Most of the major milestones from this period take place in the Gulf of Mexico. According to environmental historian Tyler Priest, the Gulf had a series of natural advantages for offshore exploitation: its waters were mostly shallow, its gradually sloping plains made it easy to experiment with free-standing structures on the open water, and the sedimentary layers on its ocean bed were relatively soft. It was also easier to gather geological information offshore than on land, where individual property holders and unhelpful landscapes could pose challenges. And these offshore fields were close enough to refineries on the Gulf Coast to ease transport of product by pipeline or barge.

In 1947, Kerr-McGee Oil Industries and two other companies hired the construction firm Brown & Root to build a freestanding offshore oil platform some 16 kilometers (10 miles) off the coast of Louisiana—the first to be completely out of sight of land, though the waters were just a few meters deep. A hurricane blew through shortly after drilling began. Yet several weeks later, the Kermac No. 16 well—now accompanied by a second platform—was generating 40 barrels of oil per hour. By 1984, it had produced 1.4 million barrels of oil and 8.7 billion liters (307 million cubic feet) of natural gas.

The Gulf hosted another global milestone in 1954 with the inauguration of the first submersible and fully transportable offshore drilling rig, which went by the name of “Mr. Charlie.” At the time, drilling in open water at serious depths remained a major challenge; rigs’ immobility entailed the risk of building expensive platforms for exploratory drilling but then finding no oil there after all.

With Mr. Charlie’s drills and other relevant machinery were installed on a floating barge, it could be towed around the Gulf in search of an exploitable site at a depth around 12 meters (40 feet). Once one was found, Mr. Charlie’s giant pontoons would be lowered and seawater would flood in until the flat-bottomed vessel settled on the seafloor, enabling safe and stable drilling. Once the job was complete, Mr. Charlie would be floated back up again, ready for the next mission.

Why offshore went global—and started heading for deeper waters

Mr. Charlie marked the beginning of a sequence of vital innovations for offshore drilling units. As offshore drilling moved into deeper waters, fixed platform rigs and then jack-up rigs—which sit on top of floating barges that extend legs down to the sea floor—were used.

In 1963, the first purpose-built semi-submersible rig was launched. Units such as these can move into location along the surface via towing or their own propulsion with huge pontoons submerged beneath them. Unlike jack-up rigs, they remain floating while drilling, kept stable by columns while the rig’s positioning is guided by thrusters and anchors. Semi-submersibles can operate at water depths of up to some 3,000 meters. Another major offshore approach—the comparatively more mobile “drillship”—was pioneered in the 1950s and 60s.

By the 1980s, Mr. Charlie was out of work, offshore drilling having moved into deeper waters than a barge could support. It now lives on as a museum and training facility. The Gulf, however, has remained a vital center for American offshore oil and gas production.

Very offshore. Swedish oil platform, circa 2018. Jan Hakan Dahlstrom / Getty Images.

Very offshore. Swedish oil platform, circa 2018. Jan Hakan Dahlstrom / Getty Images.

Since midcentury, meanwhile, other offshore hotspots have also emerged. Azerbaijan—home, by some accounts, to the world’s first oil wells—built up a vast settlement named Neft Daşları. This complex of wells and platforms (with facilities and housing) sprawls across the surface of the Caspian Sea, connected with pipelines and bridges and held up by metal poles. Technological advancements and international agreements (most notably the legal division of the continental shelf) coupled with the discovery of large offshore oil and gas reserves in the North Sea from the 1960s onwards have established Norway and the United Kingdom among other major European offshore players.

Other major offshore fields today include those off the coasts of eastern Canada, parts of Brazil, Russia’s Sakhalin Island, and West Africa. The Arabian Basin is home to significant recoverable reserves. As offshore has gone global and deepwater, its share of global production has expanded rapidly. The total production of offshore oil grew from next to nothing in 1947 to about 14% of global supply in 1974 to around 33% in 1996.

What are the opportunities and challenges for offshore oil and gas today?

Compared to the days of Mr. Charlie, operations now take place on a radically different scale: stronger, larger structures in deeper water.

Contemporary drillships can operate in depths of over 3 kilometres with maximum drilling depths of 12 kilometers or more. Troll A, a huge Norwegian gas platform in the North Sea, was the tallest concrete structure ever moved when it was towed into place in 1995. In 2015, Rosneft announced that it had drilled “the world’s longest well” off Sakhalin, reaching a measured depth of 13,500 meters (about 8 miles) and a horizontal reach of 12,033 meters (about 7 miles). And until the construction of the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, it was believed that the tallest freestanding structure in the world was the Petronius oil platform southeast of New Orleans.

Today, offshore oil and gas faces a range of significant challenges. Environmental concerns, which have dogged the industry for decades, remain in the public eye—exacerbated by high-profile disasters like the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010. Deeper waters involve even starker challenges regarding worker safety and human resources. In regions like the Arctic and the Middle East, too, offshore resources seem likely to involve geopolitical risk into the future.

At the same time, a new wave of technological innovation (plus rising demand) has been driving opportunity offshore. Remotely operated vehicles—that is, underwater robots, some of them four-legged—are used throughout the industry, while automated rigs, rig fleets, and drilling systems may offer improvements to efficiency as well as safety. High-tech environmental monitoring tools also bear promise. These innovations take on particular importance as oil and gas production moves into ever deeper, ever choppier waters.

And if they don’t work out as oil rigs, there is always the option of pivoting to tourism. In 2021, Saudi Arabia announced plans to convert an oil rig into a massive theme park and resort, with multiple hotels and restaurants along with skydiving, zip lines, and rollercoaster rides. What began way back in Summerland may end up with an amusement park.