A.C. v.s. D.C.: The macabre story behind the birth of the American grid

Posted: September 08, 2025

“He died this morning under the most revolting circumstances,” reported the New York Times in 1890 of William Kemmler, an alcoholic, illiterate vegetable peddler who, the previous year, had murdered his girlfriend with a hatchet. His execution, the report continued, “was a disgrace to civilization.”

It was supposed to be exactly the opposite. Kemmler was the first man to be executed with the electric chair, a new technology that had been adopted by the New York state legislature earlier that year on the grounds that it was more humane than hanging.

Kemmler’s execution, however, did not go to plan. The first shock didn’t quite kill him; the second killed him much too much. “Blood began to appear on the face of the wretch in the chair. It stood on the face like sweat,” went the Times report. Overheating electrodes seared his skin and singed his hair. “The stench was unbearable.”

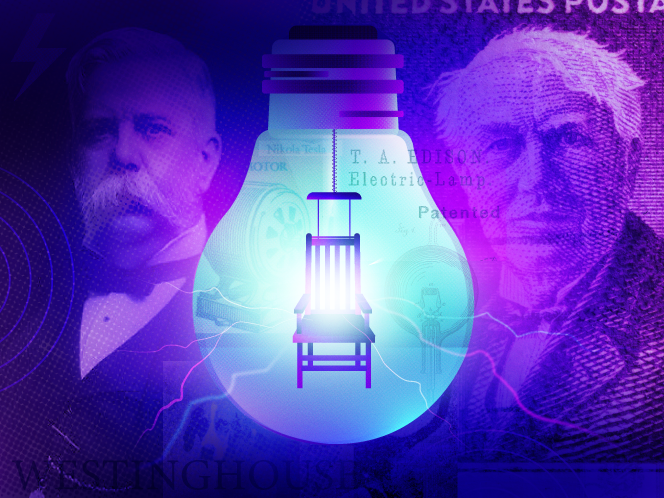

On its own, Kemmler’s death would be a grisly curio of history. But his botched execution was more than just another story of a bad man killed badly: it represented the lowest point in a bitter feud between two of the most consequential men in America.

Those men were Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse. At stake was the make-up of maybe the most transformative technology the world had ever seen: the electric grid.

Our Industrial Life

Get your bi-weekly newsletter sharing fresh perspectives on complicated issues, new technology, and open questions shaping our industrial world.

Edison’s D.C. vision: Pearl Street and early power

The adoption of the electric chair in 1890 would have been unthinkable just a decade before, when electricity was only really used to power an early—and incredibly bright—form of street lighting. In 1879, however, Thomas Edison invented the filament lightbulb. This new light was dim enough for indoor use and, as one early advert for the bulbs exhaustively outlined, was superior to existing, gas-powered lamps in every way:

“The disadvantages of gas are: sulphur thrown off, ammonia thrown off, air consumed, unsteadiness of light, danger from suffocation, danger from use of matches, expense from leaks in pipes, metals tarnished, carbonic acid thrown off, sulphurated hydrogen thrown off, atmosphere vitiated, colors made unnatural, excessive heat produced, danger from leaks in pipes, danger from fires, blackening of ceilings and decorations, freezing of pipes, water and air in pipes.”[1]

Indeed, electric light was so superior to the existing gas-powered indoor lamps that it kickstarted the retooling of urban gas infrastructure around electricity and the development of electricity-generating power plants.

Edison wasn’t just responsible for the lightbulb—he was also the primary force behind the build-out of electric power infrastructure. In 1882, he opened the Pearl Street power station, which brought together the existing electrical innovations of the century, plus a few more of Edison’s own making.

Within just two years of Pearl Street’s opening, there were 18 similar power stations in operation across the U.S., all either directly owned by Edison or running under license on his D.C. (direct current) system.

Westinghouse, Tesla and the rise of alternating current

The electric chair that killed Kemmler, however, was not powered with direct current: the generator was supplying alternating current.

This competing system had begun to gain a foothold in 1886, after George Westinghouse acquired the U.S. rights to various European alternating current patents, as well as the rights to Nikola Tesla’s induction motor.

The main advantage of the Westinghouse-backed A.C. system was the ability, through transformers, to increase and decrease the voltage of the current. Increasing the voltage made it cheaper to transport electricity over long distances, which in turn meant A.C. power stations could supply electricity to customers within a far larger radius than their D.C. equivalents.

The downside, said proponents of D.C., was the mortal danger that high-voltage A.C. lines posed to the public. An 88-page pamphlet published by the Edison Electric Company in 1886 claimed that there had already been “frequent and altogether unnecessary loss of life in Europe as well as in the United States” due to high-voltage cables strung up by cavalier “advocates of cheapness.”[2]

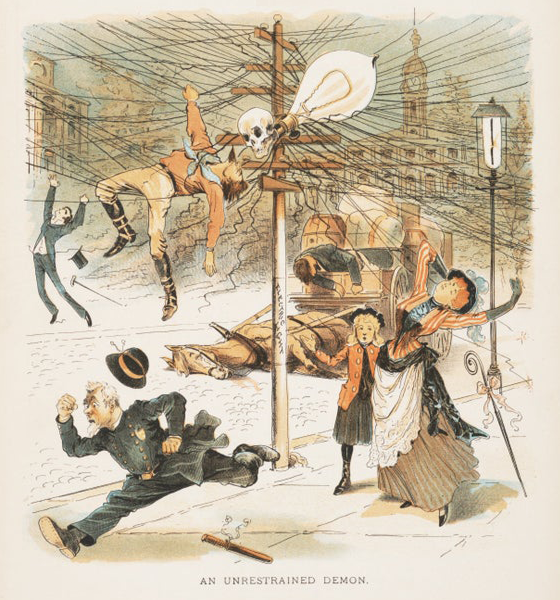

The October 1889 cover of Judge Magazine. Earlier that year, John Feeks, a Western Union employee, was killed by a high-voltage A.C. line. His death sparked a public panic about the dangers of overhead power lines.

The October 1889 cover of Judge Magazine. Earlier that year, John Feeks, a Western Union employee, was killed by a high-voltage A.C. line. His death sparked a public panic about the dangers of overhead power lines.

The danger of overhead power lines was real but it was their chaotic and unregulated installation, rather than alternating current, that was to blame. That didn’t stop people in the D.C. lobby from suggesting otherwise, of course, and the most unscrupulous of all these people—the person who would go further than anyone else to “prove” the dangerousness of A.C.—was a man by the name of Harold Brown.

Harold Brown electrocutes dogs

As 800 volts bolted through its body, the St. Bernard puppy went stiff as stone. After three seconds, Harold Brown closed the circuit, the current stopped, and the little dog collapsed, dead.[3] Brown considered this evidence that A.C. was indeed more deadly that D.C., for the dog had a few minutes before been comprehensively shocked with 200 volts of direct current and left “entirely uninjured.”

Brown was not a scientist. He ran a shop in Manhattan that sold and repaired D.C. electrical equipment. Just a few weeks before, he’d had a letter published in the New York Post denouncing A.C. as “damnable” because it submitted the public to “constant danger from sudden death.” Now, he found himself in Edison’s famous Menlo Park lab, with its equipment and staff at his disposal.

Over the weeks that followed, Brown would conduct experiments on dozens more stray dogs. Eventually, and predictably, he reached the conclusion that just 160 volts of A.C. “was instantly fatal, while with the continuous [direct] current, no injury whatsoever resulted from a pressure of 1,420 volts.” [4]

The experiments were scientifically worthless—they proved nothing except Brown’s own cruelty—but, for the New York state commission looking into a gaffe-proof means of executing criminals, the timing of Brown’s findings was perfect. Here, it seemed, was credible evidence that alternating current was a highly efficient way of killing a man.

For Edison and Brown, New York state’s decision to use A.C. was a P.R. victory. It became a rout when Brown, purchasing through intermediaries, made sure that the generator powering the new, killer chair was manufactured by the Westinghouse Electric Corporation.

The current war turns: General Electric, the World’s Fair and Niagara Falls

Edison may have won the Kemmler battle, but he was losing the current war.

“In October 1888 alone,” writes Nichol, “Westinghouse received orders to power 45,000 lights on the A.C. system, about what the Edison companies had sold for the entire year on the D.C. system.” [5] By 1890—the year of Kemmler’s execution—A.C. Westinghouse power stations outnumbered D.C. Edison stations by 323 to 202.[6]

Then, in 1892, Edison lost control of his company. It had been a long time coming. The electricity market was maturing: small outfits set up in the early 1880s were, by the end of the decade, merging with and acquiring one another.[7]

Seeing this new market structure take form, Edison’s financial backers (among them J.P. Morgan) pushed through a merger with the Thomson-Houston Electric Company. They called the new company “General Electric”—a name that has endured to this day. Edison retained a seat on the company’s board, but his influence was much diminished. There was, accordingly, a change of stance within the company. Out went Edison’s faithful devotion to D.C.; in came an appreciation for the benefits of A.C.[8]

There would be more skirmishes in the war of the currents: the bidding war between G.E. and Westinghouse, won by the latter, to light the 1892 World’s Fair in Chicago; the installation of A.C. equipment at the hydro power station at Niagara Falls in 1895; Edison’s public electrocution of a former circus elephant (with alternating current, of course) in 1903. In hindsight, however, A.C.’s triumph was assured by the mid-1890s—and maybe even as early as Kemmler’s execution.

D.C.’s comeback: Solar, batteries and H.V.D.C.

“Under the Edison system, every hamlet in the country would have its own self-contained D.C. power station, serving local needs, like the village blacksmith or butcher,” explains Nichol in AC/DC. “The Westinghouse A.C. system, by contrast, was conceived on a national scale, more like the railroads with which George Westinghouse was so familiar—a large network of long-distance routes.”[9]

During the twentieth century, Westinghouse’s vision proved the more compelling—but the pendulum is now swinging back towards Edison’s more provincial conception of electrical infrastructure. Behind the turn is the rapid growth of D.C.-generating renewable electricity sources (especially solar), plus the growth in rechargeable batteries, which run on D.C.

Direct current is even muscling in on long-distance transmission. High-voltage direct current lines are increasingly being used in place of standard A.C. lines, particularly for transportation of renewable electricity over ultralong distances (like marine interconnections).

Now, with the grid undergoing its most profound reconfiguration since its inception, A.C. might soon be fighting for its relevance in much the same way that Edison’s D.C. systems were at the end of the nineteenth century.

[1] Quoted in AC/DC: The Savage Tale of the First Standards War, Tom McNichol, p. 57.

[2] “A Warning,” Edison Electric Light Co., p. 26.

[3] Information in this section comes from Chapter 7 of AC/DC, pp. 87–106.

[4] Quoted in AC/DC, p. 102.

[5] AC/DC, p. 114.

[6] Adam Allerhand, “A Contrarian History of Early Electric Power Distribution,” in Proceedings of the IEEE.

[7] Brian Potter, “The Birth of the Grid,” in Construction Physics.

[8] W. Bernard Carlson, “Competition and Consolidation in the Electrical Manufacturing Industry, 1889-1892,”

[9] AC/DC, p. 121.